Taylor Reichelt is a recovering heroin addict.

He grew up with both his parents and a brother. He says he had a fairly normal childhood in Los Angeles but suffered from low self-esteem.

“I had a lot of anxiety as a kid,” Reichelt said. “I felt like I was adopted and I didn’t really feel like I fit in anywhere.”

Reichelt was introduced to marijuana at the age of 12 by a friend who was selling drugs at school.

“Very shortly after that, I had the opportunity to smoke crack,” Reichelt said. “I wanted to be cool, so I said yes. I thought I had found where I fit in so I decided I was going to try every drug there was.”

Reichelt began using on a daily basis and was often high during his classes.

“I started drinking heavily and taking ecstasy,” Reichelt said. “At about 18 or 19, I got introduced to painkillers. That’s really when the trouble started.”

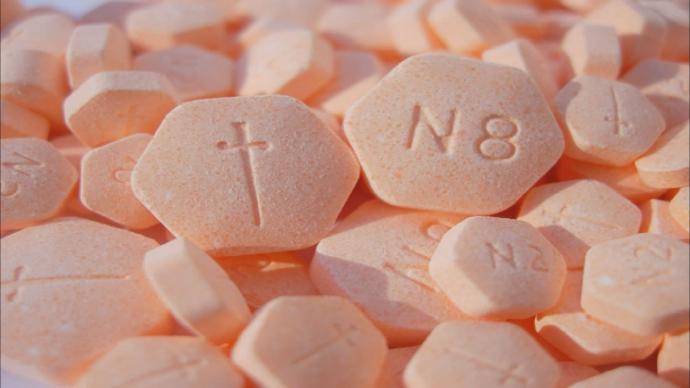

Drugs quickly took control of Reichelt’s life. Next he was on to opioids like Norco,Vicodin and Percocet.

After two years on painkillers, Reichelt switched to heroin because it was cheaper.

“The pills were expensive,” Reichelt said. “Eight pills a day at $30 a pill; that adds up.”

Reichelt was initially smoking heroin, but soon switched to needles which he used for both heroin and methamphetamine. After five attempts at rehab, Reichelt said he “woke up at 27 with nothing.”

“When I was a kid I was taught that junkies always ended up homeless with AIDS pushing a shopping cart,” Reichelt said. “On the painkillers when that stuff didn’t start happening, I didn’t think I had a problem so I was in denial. When I started taking heroin, that kinda made me think I might have a problem, but I didn’t care.”

Today, at 29, Reichelt is sober and works at a treatment center helping other opiate addicts recover. Reichelt had the opportunity to get sober and live a productive life, but thousands of opiate users will not.

According to the Center for Disease Control, there were 52,404 drug overdoses in 2015. Of those, 33,091 involved an opioid. The crisis has become so severe that President Donald Trump declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency in October of 2017.

Despite efforts of law enforcement officers and local activists, the opiate crisis has continued to worsen in Orange County. OC is one of the hardest hit counties in California, and has experienced rising drug arrests and overdoses. The relatively recent influx of highly potent synthetic opiates has contributed to those increases.

According to the Orange County Health Care Agency, 1,500 residents on average are treated for opiate-related overdoses in emergency rooms every year. The number of drug-related arrests in Huntington Beach, for example, has steadily increased from 823 in 2011 to 1,015 in 2015.

During the same period the number of opiate-related emergency room visits jumped from 1,155 in 2011 to 1,768 in 2015, according to the OCHCA.

Orange County’s southern cities saw a 21 percent increase in overdose deaths and the central cities saw a 20 percent increase, while northern cities benefited from an 18 percent decrease. Meanwhile, the overdose death rate for the homeless increased by 70 percent, according to the agency.

The OCHCA also reports that cities with higher rates of opioid prescriptions tended to have more emergency room visits and overdose deaths.

Director of the Orange County Sheriff Crime Lab Bruce Houlihan is pushing for new laws to address the opioid crisis. One such piece of legislation seeks to control access to painkillers and ensure that the pills are only prescribed to those who really need them, like patients with terminal illnesses.

He said he hopes to reign in the influx of synthetic opiates like fentanyl, which is used as an elephant tranquilizer and is far more potent than heroin.

“There’s recently been a much higher volume of fentanyl being shipped in from overseas,” Houlihan said. “It comes in large quantities in pill form and it often gets laced into heroin.”

Houlihan said an increase in public awareness and safety on the part of first responders is important. He also said the recent advent of naloxone, which can save lives from overdoses, is an example of positive work being done to combat the crisis.

Local activist Jodi Barber has been raising public awareness of the opioid crisis in Orange County since her son and several of his friends all died from overdoses in 2010.

“I wanted to stop this from happening to other families,” Barber said. “I didn’t want other families going through the same devastation.”

Barber has taken many avenues to address the opioid crisis.

“I’ve gone to Sacramento and DC. I’ve gone to rallies and helped pass laws,” Barber said.

Barber gathered signatures for the Good Samaritan Law that allows people to call for emergency response to overdoses without fear of being arrested. She produced two documentaries, “Overtaken” and “Overtaken 2,” about the crisis and shows them regularly at high schools throughout Orange County.

“I’m trying to educate and spread awareness that we have this epidemic going on,” Barber said.

Barber said doctors should be required to use a resource called the CURES Database, which keeps a record of prescriptions in California for Schedule II, III and IV drugs. The database aims to help doctors prescribe medication responsibly.

“We need to stop the over-prescribers,” Barber said. “We need to keep [opioid pills] out of people’s hands. The pills are expensive. People get addicted, they’re craving their fix and then they go to the street heroin, which is much cheaper. Now we have the fentanyl out here and that’s even deadlier than heroin. That’s a big reason more people are dying.”

Barber also said she would like to see law enforcement take complaints about dealers more seriously.

“In 2010 when my son passed, his friends told me about a woman in her 60s who was handing out pills to kids right by a middle school,” Barber said. “If they would walk her dog, she would give them Xanax and Norcos and I kept complaining to the sheriff asking him to do something. Even the neighbors put up a sign that said ‘A drug dealer lives here,’ and they weren’t doing anything about it.”

Huntington Beach Police Department Public Information Officer Angela Bennett said complaints are registered by the department and forwarded to the narcotics unit, detectives who investigate complaints and proceed with enforcement as necessary. Bennett said these investigations can entail surveillance and undercover work. Bennett also said that HBPD may consider supplying officers with Naloxone in the future.

“Naloxone is not standard issue for HBPD officers at this point,” Bennett said. “The fire department and medics carry naloxone and they are usually the ones to respond to overdoses. Police departments are moving toward making naloxone standard and it’s possibly in the works at HBPD.”

Bennett declined to elaborate further, saying she was unsure of when or how naloxone might be standardized at the HBPD. She also said the police department is working to get fentanyl off the streets.

Dr. Dan Headrick, addiction specialist and owner of the Tres Vistas Recovery Center in Laguna Beach, has been working in addiction medicine for 30 years. In Headrick’s view, there is a stigma surrounding addicts that makes people less inclined to care about them.

“One-hundred and forty-three people in the U.S. are dying every single day of opiate overdoses and nobody is doing much,” Headrick said. “Addicts don’t count. People still think it’s willful misconduct. They don’t look at it like a brain disease.”

Headrick said opiate addiction is partially willful misconduct, but a lot of other “chronic, life-threatening, treatable but not curable diseases” are too.

“That’s the definition for hypertension, arthritis, diabetes and obesity,” Headrick said. “For some reason a lot of people, even doctors, haven’t accepted drug addiction in the same way.”

In regard to emergency room response to overdoses, Headrick claims that not enough is being done after patients are treated for an overdose. Headrick said one solution may be the drug buprenorphine, which is used to temporarily treat opioid addiction.

“You just put somebody into withdrawals and then you walk them out to the parking lot,” Headrick said. “They’re using again within 20 minutes. I’m recommending that we give them a week’s supply of buprenorphine and find three places that are open to give them a bridge to get into treatment.”

Headrick also took issue with the label of “epidemic,” saying that the terminology implies that addicts are “dirty” and “infectious.”

“I call it industrialized manslaughter,” Headrick said. “This manslaughter was created on purpose for profit by the corporations like Big PhRMA who lied and deceived the public and doctors about the benefits and safety of opiates.”

Headrick cited a 2006 lawsuit in which PhRMA admitted to fraud and paid $600 million in damages.

“That same year they made $2.6 billion in profits, so it really didn’t matter to them,” Headrick said. “They just kept making oxycontin.”